The reasons behind American involvement in the Vietnam War were unclear to many but for the 2.5 million Americans who served, the one thing that was clear was that it could be a challenge to stay alive.

In the beginning of American military involvement, in 1964, fewer than 50 percent of Americans had ever heard of Vietnam. What they had heard about the country was about the battle between democracy and communism that was taking place in that small Far Eastern nation. Communism was one thing that most Americans were aware of as a result of the Red Scares of the 1950s and the domino theory was prominent—the thought that if one nation became communist, those surrounding that country were also likely to follow. Despite that knowledge, and although most Americans were aware of the threat of communism, the attitude seemed to be that this situation was so far away that there should be no reason to worry about it.

It was in 1954 that the United States started helping out in Vietnam when a treaty divided the country in two with communist China and the Soviet Union supporting the North and the United States supporting the South. The fear of the spread of Communism resulted in U.S. presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and eventually Johnson, sending support to South Vietnam in the form of military and financial assistance and this gradually escalated over the years.

By 1964, the North Vietnamese (NVA) and the Viet Cong (VC) were becoming ever more aggressive in attempts to overthrow the South Vietnamese government and the conflict escalated from there. As August 2, 1964, approached, things within this conflict were soon to change with this being the date of an alleged attack on the USS Maddox by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin. Another attack supposedly followed and the United States saw this as an act of war from the North Vietnamese. The result was that on August 7, 1964, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorizing President Johnson to take all steps necessary in Southeast Asia to protect American interest.

There is a great deal of controversy about these “attacks” and what really happened but suffice it to say, they were supposedly the rationale behind the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and history then happened. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong saw this resolution as a statement of war. The result was attacks on American air bases which resulted in the killing of American soldiers as well as the wounding of numerous others. Johnson authorized the bombing of North Vietnam to show American power, and many actually thought this war would be over in a matter of eight weeks. But with these bombings, troops that were located within South Vietnam became susceptible to VC attacks. To protect them, Johnson allowed ground troops to enter South Vietnam. It quickly became apparent that the conflict was growing into something larger than originally anticipated. And as we all know, this conflict became known as the Vietnam War. It lasted for years resulting in the deaths of 55,000+ Americans by the time it ended. Needless to say, the entire chain of events was much more prolonged and complicated than has been summarized here. Regardless of these several decades of events, America was in a war in Vietnam.

With that said, as in previous wars that have been discussed, Native Americans were very involved, having had the highest record of service per capita of any ethnic group serving in this war. More than 42,000 Native Americans served in Vietnam. While looking at a website (www.californiaindianeducation. org/wall_of_faces), PTT found that there are 232 names that identify American Indian and Alaska Native service members who were killed in action (KIA) or missing in action (MIA) during the Vietnam War. Out of these 232, six of these men were from Wisconsin.

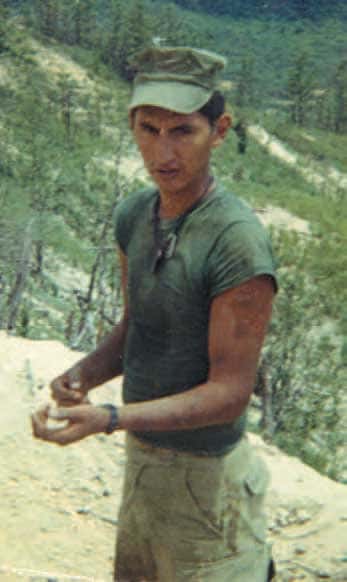

One man who knows about Vietnam and who can explain the harsh reality of what war is really like is FCP tribal member, Ernie Wensaut. PTT had the honor and privilege of hearing Ernie’s story, and being from a generation who had only heard of this war in school and from books and movies, there are no words to explain some of the horror experienced, the sacrifices made, or the courage shown by this man as he served his country during this war. continued from pg. 1

Wensaut was drafted into the service. Of course, this means he did not volunteer to be a part of this, but as he said, “I didn’t want to go but I had no choice.” This, unfortunately, was the way for many young American men during this time. Wensaut was in Vietnam from October 1966 to October 22, 1967. During this year he experienced what only those who have been in combat can explain and understand.

His age at the time was 21. At this age, most young men of his generation were out of school and starting their lives. They were finally able to get into a bar and drink legally, and it was a period of good times with buddies and girlfriends. When he was 21, Wensaut wasn’t doing those things but was fighting to survive and to keep the buddies who were with him alive. It is truly impossible for those of us who have never been there to understand war and all it involves for the individual. As Wensaut said, “It’s not fun being in a war; it’s not like it’s portrayed on TV. It’s something you live and then have to live with the rest of your life and that’s the hardest.”

Wensaut was part of the Co C 2nd Battalion 10th Infantry 1st Division (a.k.a Big Red One). He was an M-60 machine gunner, which meant he was a part of a team of two to three men who would work together in firing this massive gun. This gun earned the nickname “The Pig” due to its size, and it would fire 500-650 rounds per minute. There was the gunner (Wensaut), the assistant gunner (AG military slang), and the ammunition bearer though sometimes there would only be the gunner and an assistant.

You can imagine what a feat it was to even get this machine gun set up and ready to fire. One recollection Wensaut has is how important it was to him to always keep his gun clean no matter what. He said that if it got wet, dusty, or dirty in any way, it could easily jam, so he was compulsive about keeping it clean so it would always be operational. He describes this very thing happening to many other M-60 machine gunners and those men never got to come home. Wensaut’s AG always told him, “I’m sticking with you, Ernie, because you always keep your gun clean—I will always be with you.” That was one of the known flaws of this gun, which was an iconic image of the Vietnam War. Though it was large and had great fire power, it was known for jamming easily if not kept free of dirt and moisture and this fact cost lives.

While in Vietnam, Wensaut was in the area known as War Zone C in the highlands along the Cambodian border. Wensaut’s infantry would go into the jungle to replace troops that were already fighting in there. Once that troop was either weaned out or had their time put in, Wensaut and his buddies would head in to help. Can you imagine walking yourself into an area where you see extreme injuries to men, as well as deceased men being carried out? When first entering this area, Wensaut remembers how hot and humid it was and describes remembering seeing the paths of the tracer bullets. He remembers the feeling of not being buckled into the helicopter and just hanging on.

He recollected that while the helicopter was turning to land in the “hot LZ” (landing zone), he looked straight down into the jungle and saw and heard the acts of war. He stated, “I knew where I was.” During this interview, Wensaut went into some depth about situations he remembers which were very emotional for him as he recalled men right next to him being shot through the chest and face. Many of these men were his friends, his buddies, and they were feeling the same way he was. All any of them wanted to do was to survive and make it home to their families. Wensaut recalls, “I made friends with these men… then I didn’t see them ever again.”

One occasion he remembers: “There were so many bullets flying around us as we were trying to get the dead and wounded into a basket lowered by a helicopter that we couldn’t do it because the VC shot the basket off the helicopter.” As a result, they then had to call in the jets to drop napalm so they could get themselves and the wounded/dead out of that area. Out of the seven men who went into this specific fight, only three came walking out of it with Wensaut being one of them. As he says, “It was no picnic.” Wensaut in large part gives credit for his safety to his spiritual beliefs and to his father and mother who prayed for him every day he was over there. His father held a ceremony for him before even going to Vietnam and Wensaut says, “He gave me a gift to keep me safe there, and I believe that’s what kept me safe.”

For most of these men, this war was just as confusing as it was to the American public. Coming home from war during that time was not what you would expect to see today when soldiers return. Today, we often have huge homecomings for the men and women who have fought for our freedoms—welcoming them home with signs, cheering, and hugs all around. But for the Vietnam veterans, it was a very different story. Wensaut recalls getting off the plane to be welcomed home with words such as “baby killer”. Imagine spending a year of your life trying to stay alive while fighting in a war you didn’t understand, only to come home and be ridiculed, dishonored, and disrespected. Wensaut says, “We weren’t that, we were survivors.”

Home was tough for many men and women returning from Vietnam. Most were not praised or thanked; many had and continue to have horrible realistic nightmares of being in the jungle witnessing their friends being killed. Many lost families because their loved ones could not understand what they had been through and had seen in their time there. Many turned to alcohol and drugs to help cope with their physical and emotional pain. The number of Vietnam Veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is felt to be about 15 percent. Fifteen of every 100 Vietnam veterans carried the diagnosis of PTSD at the time of the most recent study in the late 1980s. (Found on U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website.)

Wensaut is very thankful to his wife, children, and tribal people for helping him through these tough times in his life and for always giving him hope and as much happiness as he could have. Vietnam will be a part of Wensaut as long as he lives; it is part of his life. He says, “You don’t forget it.”

Wensaut earned the Vietnam Service Medal with Bronze Service Star and a National Defense Service Medal.

FCP tribal member Ken George Sr. also knows of this horrific war on a personal level. George also honored PTT by allowing time to sit with him and talk about his time in Vietnam and about some of the things he went through.

George was in the 3rd Marine Division, Lima Co, 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, and 3rd Recon. He enlisted in the Marine Corps at the age of 19 in 1965. His reasoning behind enlisting was that during those days, there wasn’t much for a young man to do around this area. He felt by enlisting he would be able to do something with his life. He knew that by enlisting during this time, in all likelihood he would eventually be sent over to Vietnam but that thought really didn’t bother him. He said that his good buddy Frank Daniels and he were planning to go over there together. Unfortunately, something got in the way of that happening, though eventually they hooked back up on the East Coast.

George was also a machine gunner with the M-60 machine gun. He said that a typical day consisted of being on watch and maybe getting a couple hours of sleep at a time. While you were getting those few hours sleep, someone else would watch your back. But in reality, everyone was always on watch. He recalls the darkness in the jungle where he was. He said, “It was so thick in that jungle that during the daytime, it was like nighttime.” George was on the 3rd recon team which meant that he and five other men would go out into the jungle and gather information at certain check points. He and his team would go out for four to five days at a time or for however long the mission took. If they found something suspicious, they would call in an aerial observer (AO) to bomb the area. George also recalled the heat that most veterans of this war remember. He said the sun was probably about 120 degrees, and the humidity was almost 100 percent with no breeze. Because of this heat and humidity, he said that the smell of the dead was intense. It was something that never went away or goes away. He also mentioned that there were two seasons in Vietnam—the hot season and the rainy season. During the rainy season he said it would get so cold at night you would think it was going to snow. Just imagine sitting in the jungle soaking wet from head-to-toe with temperatures that are comparable to what we may see here in winter.

George also talked a bit to me about the Vietnamese guerrillas saying, “They could be friend during the day, but at night they were your worst enemy.” He also stated, “The reason these men were so good at what they did was because they were in their own backyard.” This certainly made sense, and a person has to wonder how they would have fared in “our” woods in northern Wisconsin were things reversed.

Speaking of the woods, George chuckled about an incident he had with one of Vietnam’s mammals while he was in the jungle. In our area, we have deer running free in the woods and we are used to that. However, Ken told me the story of how he was in the jungle and heard a loud pounding and could feel the ground shaking and all of a sudden, “A tiger ran right past me!” Yes—a real tiger—a huge animal bigger than any bear we would see here. We had a great laugh over this part of the interview though it was likely not too funny at the time.

George remembers his closest call during combat occurring while being in handto- hand combat with an NVA solider. Relaying the story of this incident in detail would be a sensitive subject. Let’s just say that George is a very lucky man. George’s story of the battle he has been in is relayed in the book called “Con Thien” which means “Hill of Angels”. Anyone interested can pick the book up and can read about what these men have seen and been through.

George’s homecoming was very similar to Wensaut’s. He said, “Those darn hippies would be out there throwing eggs at you and calling you “baby killers”. These men fought to stay alive and they didn’t kill babies because a baby couldn’t shoot a gun at you.” It is incredibly sad to think that these men put their lives on the line only to be welcomed home as they were. It makes your heart hurt to hear such things. George feels very fortunate to have gone through what he did and to be where he is today. He told me, “I have a purpose here; that’s why I feel I’m still here after all of that.” He’s right—George has gone on to be a chairman for the tribe and also vice chairman. He is still working as FCP Gaming Commissioner for the tribe.

Ribbons George has earned are the Bronze Star with Combat V, Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry, Vietnamese Service, Vietnamese Campaign, Presidential Unit Citation, Firewatch, Combat Action, Good Conduct, Recon Wings, and two Purple Hearts.

It should be mentioned that both of these men have seen at least 10 times more than has been relayed in this article. If everything they shared was included in this piece, it would be too horrific for many of our readers. It was a horrifying war and PTT has great respect for their personal sacrifices and sincere appreciation for their willingness to share their experiences as part of this article.

A number of other FCP tribal members served in combat during this war, though I did not have the opportunity to sit down with them and hear their personal histories. A few others of which PTT is aware are JR Holmes, U.S. Army, Specialist 4, who served in Vietnam from 1967- 68; Archie Nesaukee, 1st Calvary Division (Air Mobile) served 1967-70; Daniel “DJ” Smith, U.S. Navy, serving in 1973; and Frank Daniels, U.S. Marines. Unfortunately, we at PTT don’t have an updated list of veterans, so many apologies for not being able to specifically note others who were involved in this war. But, no doubt there are others with many stories of their own.

The Vietnam War was considered to have ended in April 1975 with the fall of Saigon and the subsequent reunification of North and South Vietnam into one country. It was a complicated war and one which the United States did not win. But the men who fought the battles of that war did so with distinction and courage unrivaled by those of any other war. As with the other wars that have been discussed in this series, the Native Americans answered the call to service without hesitation and in numbers per capita that were higher than any other ethnic group in the country. This war seems more personal to many of our generation because we know people personally who are friends and family who took part in combat during this time, and these individual recollections really bring the horror of war home. The Vietnam War marked a change in attitudes in this country about war and left a lot of deep scars in individuals and the country as a whole. And without question, the rest is history.